Art and The Church

Reflections by Dani Camarena

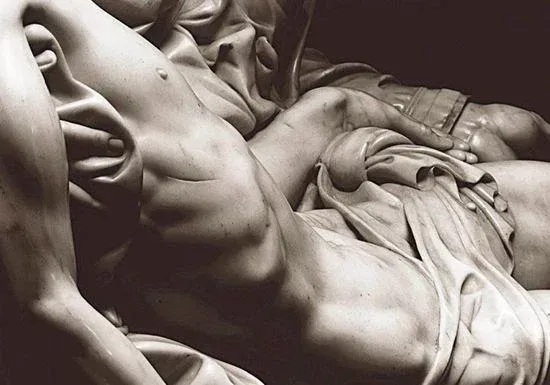

Pietá (Our Lady of Pity)

Made in 1498-99 by Michelangelo Buonarroti

Many are familiar with Michelangelo’s Pietá. It is a High Renaissance sculpture that depicts Mary’s sixth sorrow: Jesus taken down from the cross, and is one of the most well known art pieces of all time, for good reason! In the popular German tradition where the classic pieta scene comes from, Jesus was usually shown as marred and mutilated by the Passion and Mary as haggard and weighed down by the death of her Son. Such was the typical depiction, but the precocious Michelangelo would change all of that was thought of when the scene of the pieta was spoken of. Not yet a name well known in the art world, and just 23 years old, Michelangelo completed this altarpiece commission for Cardinal Jean de Villiers du Lagraulas as one of his first major works; a feat that cemented his position in the art world, and changed the genre of this scene forever.

Michelangelo never rendered another piece of stone to the degree that he did to the Pieta. It is his most detailed and meticulously handled work. The stone is polished in a way that seems to shine from within; its reflectivity and perfection reminding the viewer that Christ is the Light of the World. Interestingly, Michelangelo had been tasked with sculpting the body of a god, the Roman Bacchus, in a previous commission, but the difference in how he handles the depiction of Christ shows clearly the respect and reverence the artist understood as belonging only to God. Christ’s body is idealized to perfection, both in proportion and in the handling of the stone itself; Michelangelo gives only the body of Jesus the honor of such attention; none of his other sculptures are polished to the degree that the body of Jesus’ is in this work. He bears no signs of the Passion, only the tiniest of nail marks. The brutality of the Passion is barely present, and the viewer is asked to consider the beauty and weight of the sacrifice as something thoroughly divine.

Likewise, Mary is beautiful, her expression is detached, serene, greatly differing from other depictions of the Pieta. She is also much larger than Jesus and is able to cradle Him in her lap, recalling their relationship as mother and Son. She must have held Him as a baby just like this. Her youth and her serenity were subjects of controversy; she seems no older than her Son and not a shadow of strain crossing her expression. This deliberate choice on the part of Michelangelo stood as a way to remind the viewer of Mary’s purity, her triumph of virginity, and her fiat; that in accepting the role of Mother of God, she understood from the start that her Son would be offered as sacrifice on the world’s behalf. Despite the great suffering of watching her Son be crucified, she better than anyone understood the restorative and transformative power of God.

Despite the sculpture seeming balanced when viewed in front, viewing it from the sides shows how Jesus almost seems to be slipping off her lap. He is set to fall forward. Michelangelo’s Pieta was made as an altarpiece for the old St. Peter’s Basilica, meaning that it would be situated above the altar during Mass. If we imagine where the Body of Christ would come to rest after slipping from the Virgin’s arms, He would be on top of the altar. This small detail shows the power art has to reveal Truth: the Body of Christ and the Eucharist are one. Anyone who attended Mass seeing this altarpiece would be able to make this connection, this beautiful work was edifying as well as gratifying to behold. Another detail of the sculpture makes clear the Eucharistic significance of the piece: Mother Mary holds her Son, but her hand only makes contact with Him through the cloth of her veil. Her Son’s body is sacred and must be treated with reverence. The cloth reminds us of a priest's humeral veil, the cloth through which a priest lifts the monstrance during the veneration of Jesus in the Eucharist during Adoration. The Eucharistic significance of this piece is clear: the sacrifice is Christ, the Eucharist is His Body, Mary’s outstretched left hand offers Him to you.

Thank you for reading this article. Art and the Church are so closely related because Beauty leads us to the Truth, and learning about the beautiful art human hands have created through the guidance of God can illuminate Truth in a new way. The power of art is such that it makes seen the unseen and edifies the mind on goodness and light. It is a great honor to have written this for you, I hope you enjoyed reading it and maybe learned something new!

God Bless,

Dani Camarena

CSUF Bachelor of Fine Arts

daniella.camarena2019@gmail.com